The previous post described how individual words “found their way” into main memory. This part of the theory describes how combinations of words work in the same situation (Strømnes, 1973).

Linguistic communication is thought to be statements about spaces. Space is defined as two or more objects (characters) that are somewhat related to one another. This definition excludes some common definitions of space, such as emotional states. The space can be thought of as “an apple on the table” or even its isomorphic counterpart (painting of an apple on the table). The concept of space in the way it is understood above is important because the rules of combining images are thought to be rules of simple geometric systems. Thus, language theory must include information about these rules. On a general level, Strømnes (1973) has presented these rules in six statements.

According to the theory, “each original state must be in some space” and “each original state must have at least one geometric isomorph”. The original state can be thought of as “an apple on the table” and its geometric isomorphic as a picture of “an apple on a table” or an (mental) image of “an apple on the table”. The image of an apple on the table is expressed in English with the words “an apple is on the table” and in Finnish with the words “omena pöydällä.” The resulting image is the same: “an apple on the table”. The image would seem to be the same regardless of language – only the means of communication (words and combination rules) differ.

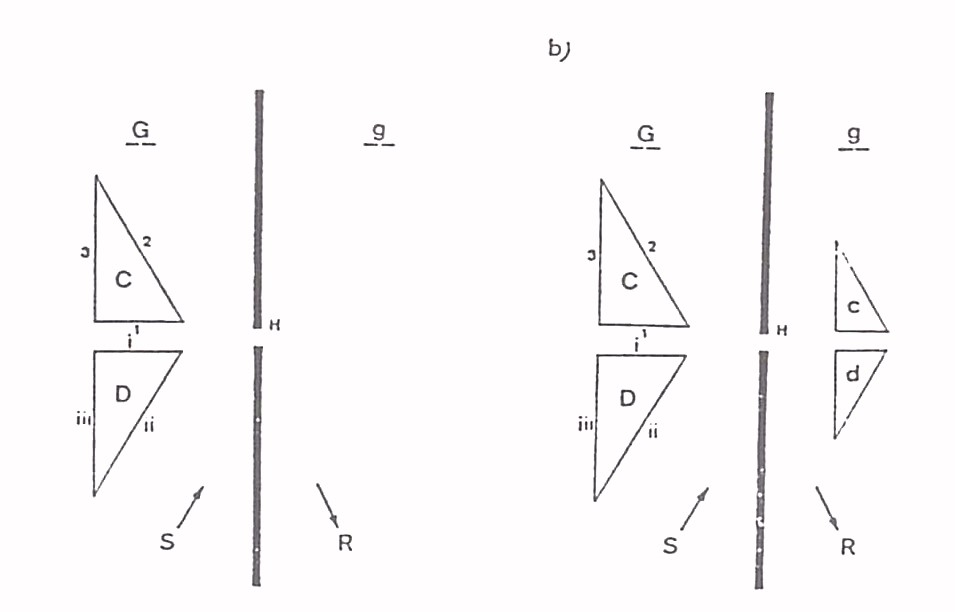

Fig. 1. The problem of information transmission through an aperture precluding transmission of isomorphic states (Strømnes, 1973).

According to the theory, the original “apple on the table” causes the viewer a corresponding isomorphic counterpart – the image of the apple on the table. In order to convey this image further to the viewer (the “sender” of the source), language must be used. If the sender’s language is English, he says (or writes) “an apple is on the table”. If the recipient understands English, he decompresses the message as shown in Figure 2 and can form an “isomorphic state” (= image) of the original state. The problem can be represented graphically (Figure 1). The problem in Figure 1 is how to transfer the triangle from the sender through the hole to the receiver to the right of the border. The hole is so small that it prevents the entire triangle from being moved. The situation corresponds to the portrayal of the image by verbal means. The prerequisite for the transfer is that the triangle is divided into parts (or transformed into a chain) and slipped through the hole with information on how to re-assemble the parts. With this information, it is possible for the recipient to assemble the correct pattern from the parts.

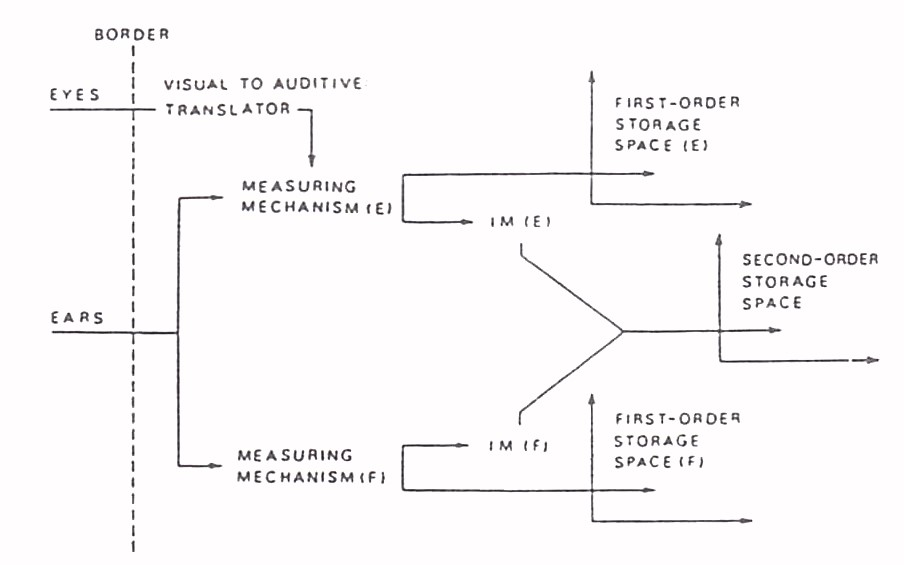

Fig. 2. A schematic model for storage of non-meaningful and meaningful material. E = mother tongue, F = acquired language (Strømnes, 1974)

Now we can return to the example “an apple is on the table”. In English, the critical word is “on”. It tells you how to combine the images of the apple and the table so that the result is “apple on the table” and not “table with apple”. In Finnish, the combination of the apple and the table images of the table is performed by adding the ending -llä to the word pöytä. In other words, in the Finnish language, the critical factor in communicating information about the space is the case-ending and in the English language the preposition.

The above presentation contained the main points of Strømnes’ theory. Here are some key assertions:

(1) Only second-order representations carry information.

(2) First-order representations are only a means of transmitting second-order representations from the sender to the recipient.

(3) First-order representations must include information on how to combine the second-order representations in order to be identical with the isomorph of the sender.

In a natural language, words are first-order representations and images second-order representations. Combination rules are transmitted in English using prepositions and in Finnish using cases. The number of Finnish cases and English prepositions is not the same. In English, 80-100 prepositions are used to express spatial relationships (Jackendoff & Landau, 1991). A preposition is not always translated using the same case. Nor can all prepositions be translated into cases. For example, the preposition “through” in the English language does not have a corresponding case in the Finnish language. Since the proper use of cases is generally very difficult for a person whose mother tongue belongs to the Indo-European language, it can be concluded from the foregoing that cases and prepositions are not based on similar spatial relationships (Strømnes & Iivonen, 1985).

REFERENCES

Jackendoff, R. & Landau, B. (1991) Spatial language and spatial cognition. In: D. Napoli & J. A. Kegl (eds.), Bridges between psychology and linguistics: A Swarthmore festschrift for Lila Gleitman. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Strømnes, F.J. (1973) A semiotic theory of imagery processes with experiments on an Indo-European and a Ural-Altaic language: Do speakers of different languages experience different cognitive worlds? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 14, 291-304.

Strømnes, F.J. (1974) Memory models and language comprehension. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 15, 26-32.

Strømnes, F.J. and livonen, L. (1985) The teaching of the syntax of written language to deaf children knowing no syntax. Human Learning, 4, 251-265.