In the early days of film, the camera was very static. In modern times the equipment is very versatile and easy to move which gives the crew many opportunities to change the point of view and follow the persons on stage in many different ways. The data presented below concentrates on the differences of the English and the Hungarian crews in their ways of doing it.

Camera following movement

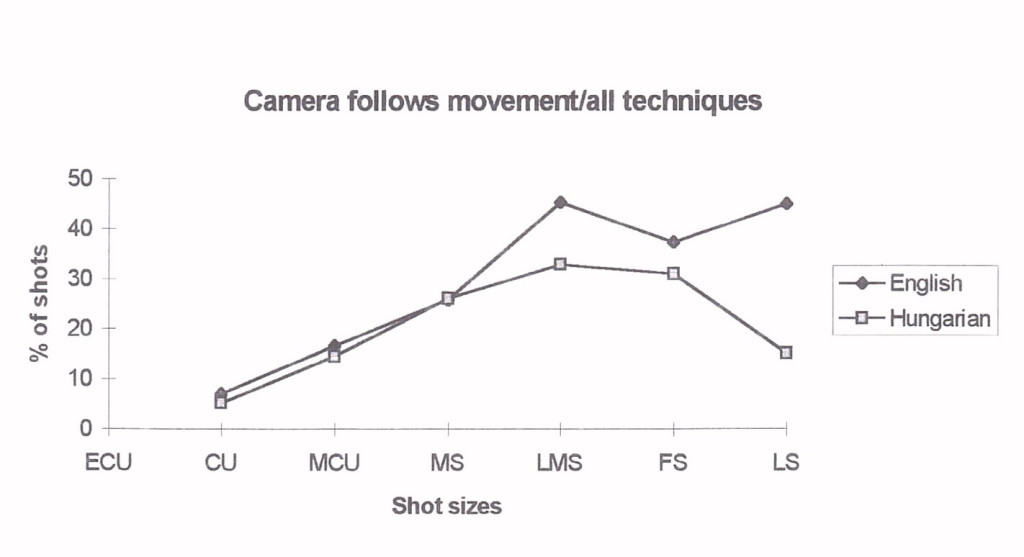

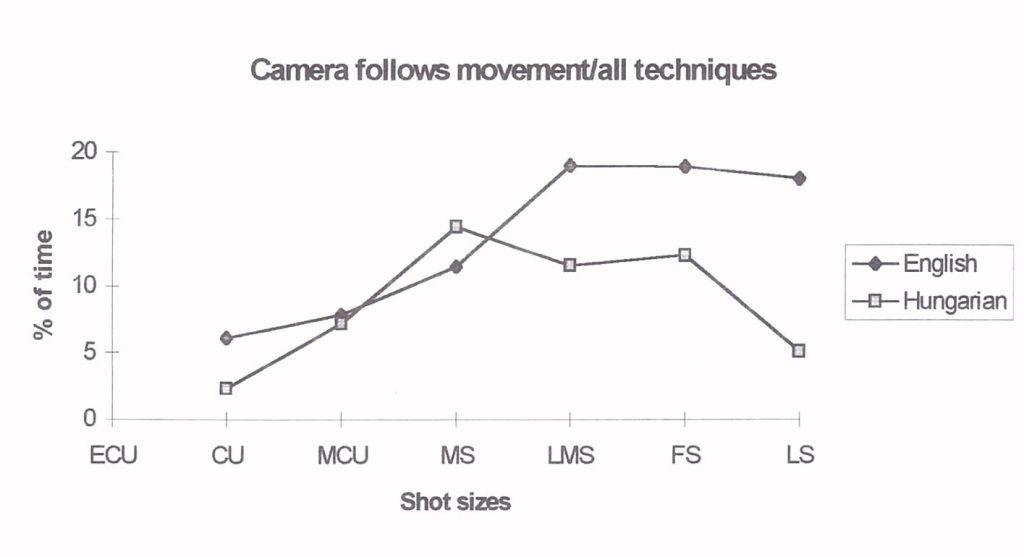

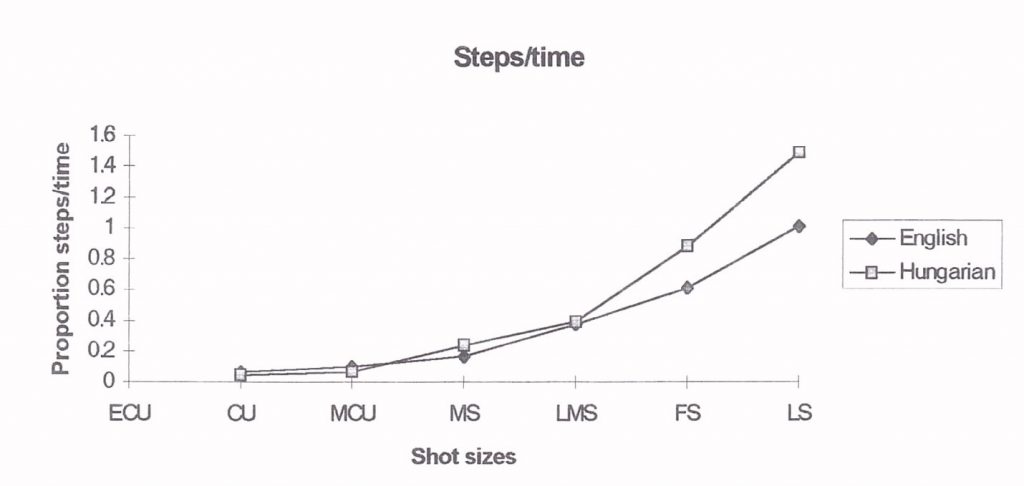

Fig. 1 shows the following of movement by the camera according to the image size in relation to the number of shot sizes [1] and Fig. 2 shows the same proportional to shot time. Analyzed in this way, the English version clearly shows more movement tracking in large images (LMS-LS) than the Hungarian version. Relative to time, there is 2-4 times more and relative to the number of shots, 50-200% more. The difference between the distributions (Figure 1) is very significant (X2 = 16.92, v = 3, p <0.001), The differences are similar to the previous study (Strømnes et al., 1982).

Figure 1. The camera follows the movement relative to the number of shot sizes. According to the starting shot size.

Differences in following movements with the camera are, except quantitative, also qualitative. The Hungarians mostly follow the movement in an expanding picture (=person leaving the situation). The review of the statistics also shows that this is the case. In the English version, the image size grows 50 times and shrinks 39 times. The corresponding figures in the Hungarian version are 66 and 17. The Hungarians follow the person leaving the situation about four times more often than the approaching person. The English version has a ratio of 5:4. The difference between versions is very significant (z = 3.26, p <0.001). This means that the English will take the incoming person into the picture already when he / she enters the room. In the Hungarian version, the actor /actress, on the other hand, often enters the picture without the viewer knowing where the person came from. Analysis of truncated movements confirms this (see below).

Figure 2. The camera following movement relative to the time available in the shot size.

People’s movements

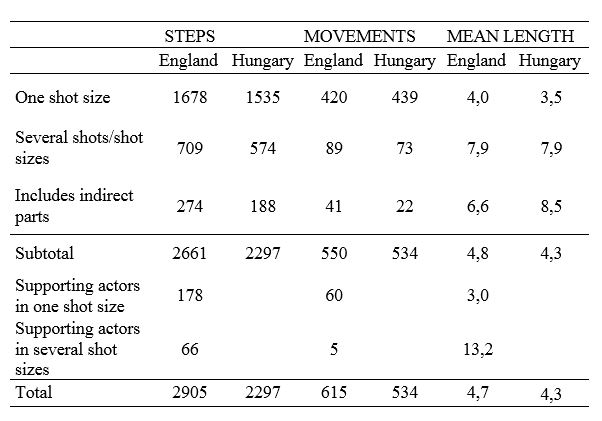

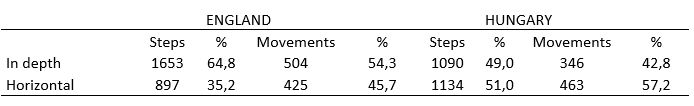

People’s movements were analyzed in a variety of ways, some of which are image-size dependent, some not. The same criteria were applied to both materials except that the movements of the supporting actors and waiters them serving in the English version were separately recorded and omitted from the analyzes. In the Hungarian version there were no people that were not directly involved in the events. See Table 1.

Table 1. Analysis of movements, overview.

Movements per shot size

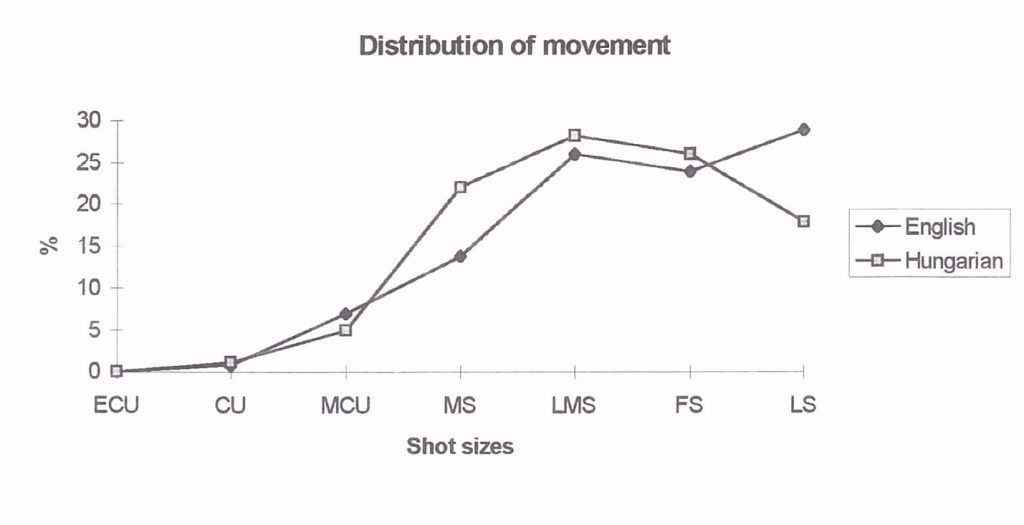

In the English version, the number of steps increases almost linearly with the increase in image size as the possibilities of 3D imaging increase (Figure 3). In the Hungarian version, on the other hand, almost a quarter of the steps are in the medium shots (MS), and fewer steps are described in long shots (LS). The figure takes into account all the steps that can be counted on the screen, except for the movements of the supporting actors in the English version and the sections described indirectly (cued movements) in both versions. The distributions are almost identical with tracking of movement (cf. Fig. 1). The difference is very significant (X2 = 115.078, v=5, p <0.0001) and in line with the results of the previous study (Strømnes et al., 1982).

Figure 3. Distributions of movements in steps.

The large picture sizes in the Hungarian version are dedicated to the description of the movements of large groups. This is apparent in Figure 4, where the number of steps is proportional to the time available in the image size. In the English version, the ratio increases steadily as the image size grows and approaches the ratio 1 step / sec in long shots. In the Hungarian version, the ratio increases steeper and is about 1.5 steps / sec in long shots. This means that more people have to move at the same time because there are times when nobody is moving.

Since both versions follow very closely the original script, it can be concluded that the selection of image size is a matter of preference and does not depend on the need to picture movement. Hungarians prefer to use close-ups, so that in scenes, where many people move, less time is left for large images and they are filled with motion. In the Hungarian version, there are more steps in relation to time than in the English version, but movement is followed less with the camera.

Figure 4. Number of steps in relation to time in each shot size.

Movements according to direction

When analyzing the directions of movement, they were separated in sections of in-depth (towards or away from the viewer) and horizontal (left or right) in 90-degree sectors. The number of directions were counted also from multi-direction movements. The combined results of the main directions are shown below.

In the English version, two thirds of all steps are in the depth, while only half in the Hungarian version (Table 2). In the English version, 54.3% of the movements are in depth and 42.8% in the Hungarian version (z = 4.78, p <0.001). As the length of the movement increases, the difference between the versions increases. Of the movements longer than 5 steps, 78.8 % are in depth in the English version while only 57.0 % are in depth in the Hungarian version.

Table 2. Movements according to direction.

Truncated movements

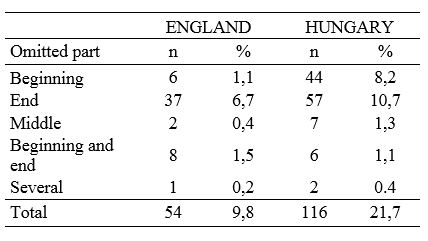

Five ways to cut off the movement were taken into consideration (Table 3). When calculating them, only the movements of the main characters and other persons directly involved in the events were considered, such as waiters bringing food to the main characters (not the dancing audience and other supporting actors in the English version). Indirectly described (cued) movements were not considered to be cut off.

Table 3. The amount of truncated movements and their proportions of all movements.

In the English version, of the movements 9.8% were truncated and 21.7% in Hungarian version (z = 5.39, p <0.001). Strictly speaking, in the English version there were only a few scenes where it was impossible to find out where the person went (e.g. waiters) and once a person was knowingly “forgotten” to the side, from where he then intervened after a moment. The movements of those who were essential to narration were always clear. Only a very small part of the beginning or the end was left out, so that the viewer could clearly see where the person came from or where he/she went. If the person left the room, the shot could be cut a couple of steps before the person reached the doorway.

In the Hungarian version, in most cases, it was impossible to find out where the person moved to when stepping out of the picture, or wherefrom he / she stepped into the picture. Often, however, the actor / actress was somewhere near to join the action when the script required it.

The biggest difference between the versions is the omission of the initial part of the movement (z = 5.65, p <0.001). The English version sought to take the person into the picture as soon as he / she moved or stepped into the room. The end of the movement was omitted 37 times in the English version and 57 times in the Hungarian version (z = 2.49, p <0.025). In the English version it was significantly more often clear where the person went than in the Hungarian version.There is no significant difference in other ways of cutting movements. The results of this analysis are very similar to the previous study (Strømnes et al., 1982).

Summary of the results

The results and viewing experiences show clear differences between the versions, in line with the hypotheses. Versions differ in terms of motion, space, and camera use. In the English version, the entire structure serves the rendering of movement in three-dimensional space, while in the Hungarian version the relationship between the characters is the starting point of the rendering. In the English version, the rendering is based on movement. In the English version the movements were shot more often in large images and more often in the depth direction. The subject of the description is the person who moves and the motion is not cut off. The viewer is always kept aware of the space and the locations of the persons in it.

Understanding the movements and location of people in the English version is easy for the viewer. In the Hungarian version, the description is based on a person or a group. In this case, it is natural for others to give way so that the people of interest are in the middle of interest. The others step into the picture again when they are needed. The positions of the people in the space of the play is far less important. We saw the same differences when we compared Finnish and other Nordic productions.

The English version has more depth than the Hungarian version. It is convincingly apparent from the statistical recordings of the protocols that the differences in depth do not just arise from the different solutions of the second act, but they are similar throughout the play. The lack of supporting actors could be thought to affect the use of the stage in the Hungarian version during the second act – mainly as a depth-reducing factor, because a wide and empty stage might seem quite odd – but looking at the staging solution it is clear that this is by no means the case. The staging in the second act of the Hungarian production is deep and narrow in structure and versatile enough to give the opportunity for deep images, but they are not used. The camera angles and other camera use favor the separation of the person from the background.

Camera use in the versions are different in terms of volume and quality. The English camera is more active – it moves more and follows movement more.

Discussion

In the previously reported study (Strømnes et al., 1982), it was found that Swedish and Norwegian imaging closely followed the rules of textbooks in preserving the unity of time and place (e.g. Burch, 1973; Martin, 1971) while the Finns departed from them in many places (Strømnes et al., 1983, 48). The three-dimensional meaning of the Strømnes’ theory (Strømnes, 1973; 1974b; 2006) must therefore be interpreted as meaning a wider three-dimensional perception of space than just as a room and its depth dimension. In the English version the team had worked hard to indicate local transitions with drawings. Random monitoring of films based on original Hungarian and Indo-European manuscripts would suggest that such differences between language groups are common. In a classic play intended to be performed in the theater, there are no written temporal transitions in the manuscript that are often typical of the drama written for e.g. television. There is probably a big difference between these countries in the way they render them, so these studies should be continued, for example, in another Hungarian – Indo-European pair.

The differences in the behavior of linguistic groups in creating visual productions are differences between highly trained individuals in activities for which they have had plenty of time to plan. The weakness of previous studies in cognitive differences has often been the large differences in the level of formal education among the test groups. In this study, the subjects have all received a long course of education, and they have had a lot of training in their field of specialization. This training is supposedly based largely on the same universal material and textbooks. However, there are clear differences between language groups.

This strongly suggests that the mental models of the different language groups differ in a systematic way, and at the same time, that the mental models of all the people speaking these languages are different. The results are in strong contradiction with the linguistic universality hypothesis and correspondingly support the linguistic proportionality hypothesis. Based on these and previous experimental studies to test the theory, it seems very likely that the language we use guides observations and image formation in a way that most psychological studies have not been able to take into account at all.

The fact that these systematic differences between pictorial materials produced in different language areas have not been previously detected may be due to a language-driven selective way of collecting information. From the continuous stream, the information needed to build our own model is selected and the rest is filtered out. Following the logical line in this direction, reference could be made to the fact that footage from the English language area, where it is easy to understand time and place, is easily accepted throughout the world. On the other hand, footage from other cultures, in which the variables of time, place and space can be handled in very different ways, feels often strange and difficult to understand. These usually don’t get large audiences outside their own cultural circles ( Strømnes et al., 1982 ; Ihamuotila, 1979).

The existence of various logical chains is also illustrated in Kaplan’s (1972) review of how foreign-language postgraduate students organize their written outputs. According to him English-speaking students write their stories as straight (time)lines from the beginning to the end. Speakers of Oriental languages write their stories as an inward spiral and speakers of Semiotic languages write their stories as a series of subordinate levels, of which each is treated in turn. In the light of the results obtained in this paper, Kaplan’s results are gaining new credibility and can shed ligth on the structures of the mental models. This study shows that by analyzing image production, one can get indications of the structural features of mental models in different languages.

This study fulfilled its purpose. It provided indications that the mental models of the Indo-European and Ural-Altaic language groups are built on different bases. The results also show that the mental structures of related languages are largely similar. The results refer strongly to the existence of structures predicted by the theory between Ural-Altaic and Indo-European imaging. Spatial relationships are formulated in pictorial communications in a language-specific manner. Together with the previously observed structures in printed and verbal communication (Strømnes, 1974a) and the results of language teaching to deaf children (Strømnes & Iivonen, 1985), these results strongly suggest that understanding concrete spatial relationships is an important part of understanding language. The results support Strømnes’ (1973, 1979) claims about the primacy of pictorial representations in processing language and it also strongly hints to the link between language structure and the creation of mental models.

[1]. For shot sizes see my previous post Recording procedure in “You never can tell”.

Acknowledgements

This work has been done in small pieces over several years and many people have contributed to the creation of this report. Without the contribution of the Finnish Broadcasting Corporation (YLE) this research would never have been possible. Pirkko Ihamuotila of the international service of YLE made a great effort in searching for material and partners in foreign television companies, the YLE film archive copied and encoded the material for research use. In particular, I would like to thank Matti Oksanen, Mikko Anttikoski and Veli Perälä, without whose help I would never have started this project. I would also like to thank the Broadcasting Center of Western Finland, whose equipment and facilities I could use during the measurement phase. I would also like to express my gratitude to the personnel of the Hungarian TV who sympathetically provided their material for use. The Finnish Film Foundation and the Audiovisual Communication Culture Promotion Center (AVEK) have supported my research with grants.

Without Erkki Hiltunen’s organizational ability and tireless drilling, all of these pieces would not have clamped into place. He was also able to do all the required measurements. He and late Martti Jännes once developed the basis of the measurement method applied in this study. With them I have had countless conversations where we solved a number of practical and theoretical problems.

To late Frode Strømnes I am grateful for all the patience he showed during those years of work. Isto Ruoppila gave me the opportunity to compile the data in the form of a research report. I am greatly grateful to him for that. Both Frode and Isto have commented on the script without which my work would have suffered many shortcomings. What the weaknesses in this work are, let them not be read into their fault.

REFERENCES

Burch, N. (1973) Theory of film practice. London: Secker and Warburg.

Ihamuotila, P. (1979) Mietteitä suomalaisesta tv-kuvailmaisusta ulkomaanmyynnin kannalta (Thougths about Finnish TV-productions from the point of view of export). Helsinki: Oy Yleisradio Ab, Julkaisematon käsikirjoitus (Unpublished manuscript).

Kaplan, R.B. (1972) Cultural thought patterns in inter-cultural education. In K.Croft (ed.), Readings on English as a second language. Cambridge, Mass.: Winthrop.

Martin, M. (1971) Elokuvan kieli (Language of the cinema). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava.

Strømnes, F.J. (1973) A semiotic theory of imagery processes with experiments on an Indo-European and a Ural-Altaic language: Do speakers of different languages experience different cognitive worlds? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 14, 291-304.

Strømnes, F.J. (1974a) To be is not always to be. The hypothesis of cognitive universality in the light of studies on elliptic language behaviour. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 15, 89-98.

Strømnes, F.J. (1974b) No universality of cognitive structures? Two experiments with almost perfect one-trial learning of translatable operators in a Ural-Altaic and an Indo-European language. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 15, 300-309.

Strømnes, F.J. (1979) The problem of the image: can there be information in propositions. Communication, 4, 259-275.

Strømnes, F.J. (2006). The fall of the word and the rise of the mental model. A reinterpretation of the research on spatial cognition and language. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Strømnes, F.J., Johansson, A. & Hiltunen, E. (1982) The externalised image. A study showing differences correlating with language structure between pictorial structure in Ural-Altaic and Indo-European filmed versions of the same plays. Helsinki: The Finnish Broadcasting Corporation, Report No. 21.

Strømnes, F.J., Johansson, A., Hiltunen, E., Jännes, M., Uosukainen, J. ja Takkinen, H. (1983) Pohjoismainen vertaileva kuvailmaisututkimus. Helsinki: Oy Yleisradio Ab, Sarja C: 2.

Strømnes, F.J. and livonen, L. (1985) The teaching of the syntax of written language to deaf children knowing no syntax. Human Learning, 4, 251-265.