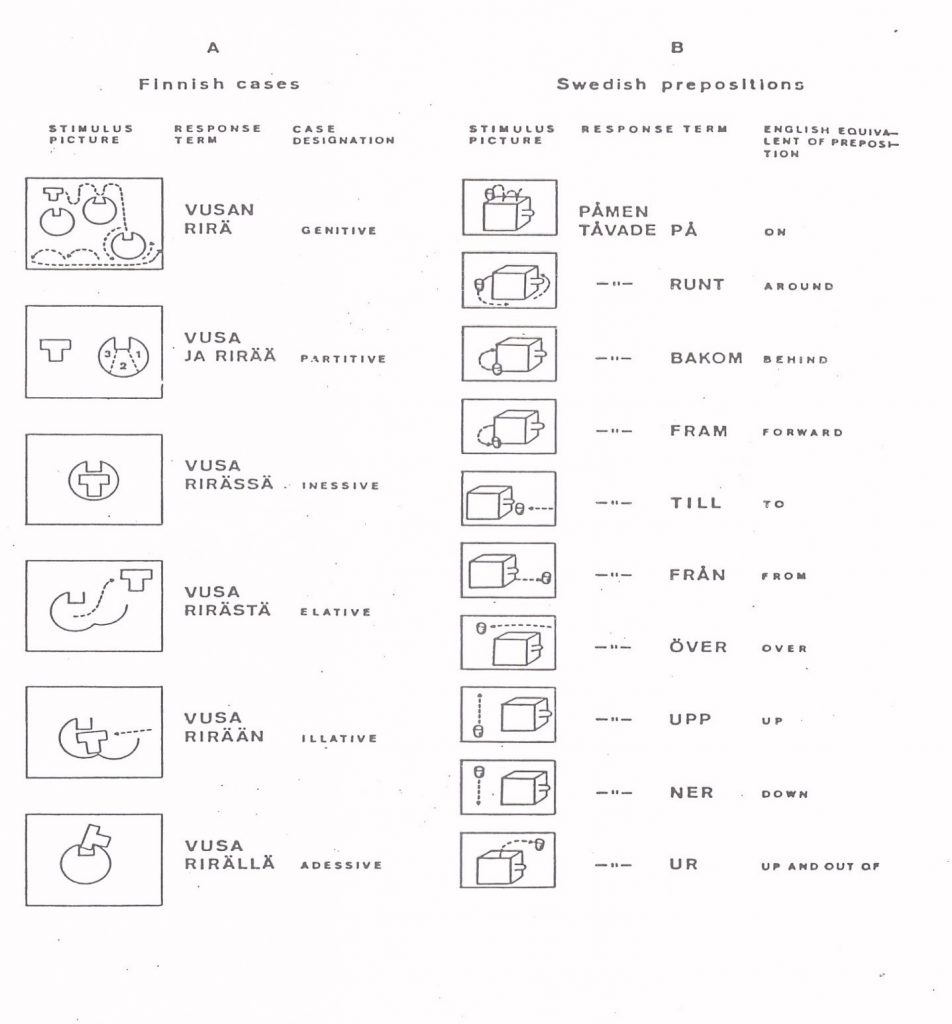

The images shown on the following pages are schematic drawings of animated films that were constructed as experimental laboratory work (Strømnes, 1974)1. It is easy to see that the systems are very different. Prepositions of the Swedish language are represented by the movement of a small character named PÅM. It moves three-dimensionally with a larger, anonymous character. The system is a simple vector geometry in which information is transmitted through continuous movements in three-dimensional space. Finnish cases can be described with two-dimensional characters, but there is a third dimension – a time that does not appear in these images. Each film had to have a certain, fixed duration that varied from one case to another. In other words, the cases of the Finnish language are based on the relationship between the boundaries of two characters and the time dimension. The Swedish language coordinate system proved to be fixed: the rules emphasized the movement of a character or characters in a stationary coordinate system (cf. car motion map). The quality of the movement and the direction of the movement are important. In other words, the importance of prepositions is in motion, which is continuous. In the description of Finnish language cases, the movement proved to be of secondary importance. The relationship between the two characters became more important. The movement was a transition from one relation to another. The characters were “equal” so that either one can be the reference character with respect to which the other’s position is evaluated. The meaning was conveyed by the position of the characters or by the change of position in a space where the coordinate system was not tied to any fixed point but the characters were compared only to each other.

Fig. 1 Examples of the spatial structures of the Finnish and Swedish languages (Strømnes, 1974).

The material was used in experiments where the subjects were Finnish-, Swedish-, Norwegian- and Sami-speaking teenage pupils. The Finnish-speaking and Swedish-speaking test subjects living in Finland[1] were students of the last two classes of the elementary schools in Turku, so they had studied Swedish or Finnish, respectively, as their second language for at least six years. The significance of the material was well-established by the fact that both Finnish-speaking and Swedish-speaking test subjects learned the material of both films almost perfectly in one trial. For Norwegian-speaking subjects, the Finnish case films were totally uninformative (on average only one correct answer of twelve). For preposition films, their performance was even better than that of Swedish-speaking subjects (on average 18.63 vs. 17.67 out of 21 on the first trial). The performance of Sami-speaking subjects (whose Swedish language teaching had been very limited) for preposition films was comparable to the performance of Norwegian test subjects for case films. Their average was 1.52 correct answers.

Due to material relevance, the normal control procedure, in which ‘false’ images and texts are combined, is tricky for the test arrangement because the test subjects may easily fix their memory images in the ‘right’ direction in the response phase. On the other hand, if the material is meaningful (as strongly assumed here) they may note that images and texts do not fit in any pair, and this again affects memory performance. Unfortunately, the experiment did not use monolingual groups that would have been shown control films, the lack of which should be considered as a defect. The hypothesis would of course be that the performance of the control group would not differ from the performance of, for example, the Norwegian-speaking subjects in the Finnish material or the performance of the Sámi in the Swedish material. According to the above assumptions, the performance of Finnish-speaking and Swedish-speaking subjects in foreign language control material should be better than in their own language material (should it have been scrambled).

Structures based on these films were later used successfully in the teaching of the native language of deaf Finnish-speaking children (Strømnes & Iivonen, 1985). Learning the syntax of the written language is a task that has generally proved impossible for people deaf from birth and with less than average intelligence (Conrad, 1977, 1979, 1981; Furth, 1966; Murphy, 1957; Norden, 1975; Savage, Evans & Savage, 1981). During one academic year, subjects (11 and 13-year-old boys whose school performance was less than average) were taught spatial relationships of the cases outside of normal classroom teaching. At the end of the year, the subjects showed only moderate advancement, but six years later they were clearly the best in their class in their verbal abilities. They communicated with their hearing friends by writing, which is quite exceptional considering their starting point. Strømnes and Iivonen had succeeded in teaching the syntactic rules of the language like any other skill. This result strongly contradicts the ideas of, for example, Chomsky (1972) and Fodor (1975), according to which each individual has innate knowledge of a universal grammar that has not to be learned. Skills in language learning of the deaf are also supported by the fact that language learning correlates directly with a person’s level of intelligence (Conrad, 1977, 1979, 1981). The smarter the deaf person is, the easier it is for him / her to detect the regularities associated with the language structure.

According to this model, the problem of language learning by the deaf is that in the normal classroom environment there is no immediate connection between spatial relationships and their linguistic expression, in which case learning is delayed or prevented. Language teaching at school is typically purely verbal or the connections to observable things are very loose. Moeser and Bregman (1972, 1973) studied this hypothesis by teaching the subjects a miniature language in two ways: the words of the tongue were displayed either alone or combined with the images they portrayed. In spite of massive training (3200 retries; Moeser and Bregman, 1973), in the “Only Words” situation, the performance of the subjects at the end of the experiment was at a random level, while in the “pictures and text” situation, the subjects were able to fully control the language syntax midway through the test series and then expand their skill by only verbal means. In the study reported by Strømnes and Iivonen, this was the case with natural language learning.

On the basis of the experience gained in the laboratory during the development of the model, Strømnes presented a hypothesis of the time structures of these two languages, according to which the internal time concept of Finnish would be relative, whereas the internal time of the Swedish language would be measurable, steadily flowing from the past to the future through the present. This assumption was based on the fact that each of the cases seemed to have a duration of its own. This duration was most favored by the subjects used in the development of the images. However, in the above-mentioned experiment, mainly animations of the same duration were used, with the exception of two positions (genitive and essive). On the other hand, the hypothesis was also based on the structure of the animations. The motion in the preposition films was mostly even and continuous, while in the case films the event had its own duration, exceeded which changed the meaning. Thus, for example, VUSA RIRÄLLE becomes VUSA RIRÄLLÄ, if the movement after the transition period stops and the film continues.

Strømnes has not done any testing of time differences, but indirect support for this hypothesis can be found in the TV-production research (Strømnes et al.,1982).

1)The original Swedish experimental film is found here: https://youtu.be/WzopFpUQghk and a later version of the Finnish cases here: https://youtu.be/xiGuzu5z8_4

Chomsky, N. (1972) Language and mind. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Conrad, R. (1977) The reading ability of deaf school-leavers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 47, 138-148.

Conrad, R. (1979) The deaf school child. London: Harper and Row.

Conrad, R. (1981) Reading: seeing, speaking, signing. In Lesen: Oslo 4-6.10.1969. Heidelberg: Groos Verlag.

Fodor, J.A. (1975) The language of thought. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

Furth, H.G. (1966) Thinking without language: Psychological implications of deafness. New York: Free Press.

Moeser, S.D. & Bregman, A.S. (1972) The role of reference in the acquisition of a miniature artificial language. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 759-769.

Moeser, S.D. & Bregman, A.S. (1973) Imagery and language acquisition. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12, 91-98.

Murphy, K.P. (1957) Test of abilities and attainments. In: A. Ewing (ed.) Educational guidance and the deaf child. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Nordén, K. (1975) Psychological studies of deaf adolescents. Lund: Glerup.

Savage R.D., Evans, L. and Savage J.F. (1981) Psychology and communication in deaf children. Sydney: Grune and Stratton.

Strømnes, F.J. (1974) No universality of cognitive structures? Two experiments with almost perfect one-trial learning of translatable operators in a Ural-Altaic and an Indo-European language. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 15, 300-309.

Strømnes, F.J. and livonen, L. (1985) The teaching of the syntax of written language to deaf children knowing no syntax. Human Learning, 4, 251-265.

Comments

2 responses to “Geometric relations conveyed by Swedish prepositions and Finnish cases”

How does the presence of visual aids in language instruction impact the language learning outcomes for deaf students compared to purely verbal instruction?

Greeting : Telkom University

It is quite simple. With hearing children the visual aids occur simultaniously with the verbal input. They hear the instruction: put the spoon on the table (in Finnish: ”laita lusikka pöydäLLE”) simultaniously with the visual aids. With deaf children this is not the case. The two boys in the beginning of the experiment had no idea that the last letters of a word in the Finnish language had any meaning because when reading there is no simultanious visual input. When the experiment was concluded the boys were the best readers in their class.

The experiment was conducted during the years 1976-1979 when there were very little possibilities to create eg. videoclips to mimic real life situations with simultaniously showing the situation and the respective syntactic structure. So cardboard was very much used to show pictures and the respective syntactic structure along with different games and other instructions to actually to something.