In the previous studies reported below, differences between language groups were sought from verbal communication. However, the differences in mental models are the underlying part of the theory. If their different structures had an impact on the formation and behavior of the mental models of persons belonging to a language group, it should most clearly appear in a task that places as little restriction on its author as possible. Such a task is e.g. implementing a visual report. On this basis, a hypothesis was made that the differences should be reflected in the cinema and television productions of the countries concerned. References in this direction had already been received from the reception of Finnish film and television productions abroad. These kinds of productions have been alienated there. Criticism has been directed at excessive length, difficulty in getting to grips with the essential contents, pictorial and narrative slowness, and the scarcity of dramatic materials (Ihamuotila, 1979), in other words, the lack of movement. The best-selling productions were made by Swedish-speaking directors, which would still indicate that it was a language rather than a resource or skill factor.

Classical plays which were similar in their basic solutions from the same manuscripts in different Nordic countries were chosen for examination. Four pairs were found for Finnish versions, three of which were implemented in Norway and one in Sweden. Norwegian versions were accepted for comparison for two reasons. First of all, not enough Finnish-Swedish pairs were found and, secondly, Norwegian and Swedish are so closely related that the speakers of these languages do not have to learn each other’s languages to understand each other. The selected pairs were examined by two different measurement methods (Strømnes et al., 1982). In the first study, the use of the camera and the amount of movement in one reference pair were observed. The movements of both cameras and persons were measured in centimeters on the surface of the screen. In the second study, the movements of the individuals were counted as steps in both directions and lengths. Pictorial depth and distances were estimated in meters. In both studies, the image sizes used were also recorded. In the first study, there was only one image size measurement was per shot, but in the second, the image size registration was refined so that there could be more image sizes per shot depending on the person or camera movements.

Based on the structure of the form and preposition animations, hypotheses were made about the expected differences. The description of the movement was expected to be dominant in the Swedish and Norwegian versions, while the Finnish versions relations between persons were expected to play a more important role. Since motion description was assumed to be important in Swedish and Norwegian versions, the camera was thought to be used differently in these versions than in Finnish versions. Since the Finnish case animations could be implemented with two-dimensional images, differences in image depths were assumed, so that in Swedish and Norwegian versions images with a depth dimension greater than in Finnish would be used. Movements in depth were present in the preposition animations, and that is why more movements towards and away from the camera were thought to be found in Norwegian and Swedish versions.

The results were as expected for both methods. In the Swedish and Norwegian versions, the movements were longer, the movements were more in depth than in the Finnish versions and the description of the movement was more accurate. The movements were almost always described from the beginning till the end. The person was not allowed to walk into an image from an unknown place or to leave to an unknown place. The viewer was always informed about where the person came from and where he/she went.

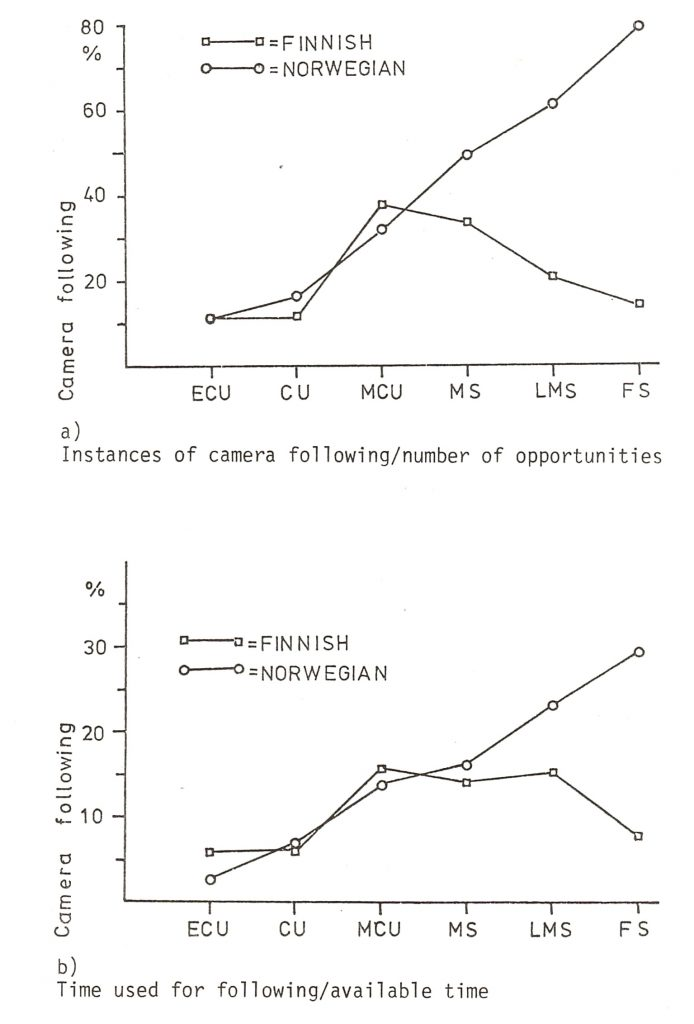

The description of the space of the drama (= apartment), the places of the persons in that space and the time of the event were clearly perceived by the spectator on the basis of the film. The state and motion variables were interrelated – the amount of movement and the movement of the camera increased proportionally as the image size grew, i.e. the possibilities of perceiving the 3D-space increased. The time flow was clearly marked by the so-called time-stamps (Martin, 1971), which tells the viewer how much time has elapsed between two successive situations, whether persons have moved to another, more distant time, or whether two sequentially described events are actually concurrent. In the first study, the use of the camera being observed was clearly different from the Finnish one. The camera followed the movements clearly more than in the Finnish versions and the more the larger the picture size was (Fig. 1).

Fig 1. Camera following movement related to number of opportunities and time avalable. Study 1: The Wild Duck by Ibsen. From Strømnes et al., 1982.

On the basis of the films, the Indo-European three-dimensional view is to be understood as a broader understanding of the space than a simple depth dimension in the pictures. It is the perception of space as a whole that opens through movement. The dimensions of motion, space, and time are thus very strongly linked to each other. Continuous motion reflects continuous time, and both are bound to universal space and time.

In the Finnish versions, the description of persons was more intense – the use of close-ups was more common and people were closer to each other. The motion was pictured in close-ups and medium shots. There were less large shot sizes than in the Swedish and Norwegian versions. Thus, in picturing a moving person, the person (and not his/her location) was of more importance. Focusing on the description of the persons was so strong that the description of space was secondary. The space of the drama was impossible for the researchers to picture on the basis of the filmed material in two plays, although schematic drawings of the studio were available. The punctuation of time was not used in plays where they were included in the corresponding Norwegian and Swedish versions. Shifts of time and space were executed by simple cuts, which according to European film theory correspond to simple changes of perspective (Burch, 1973). In these situations, the viewer found out only much later that the time and place had changed.

According to Strømnes (1973, 1974), there was a clear conception of time in the films depicting Finnish cases. On the other hand, from the Finnish films studied, the time description was missing in a form that would be understandable to foreign audiences. Likewise, the positions of the figures are very important in the case films, but there was not always exact information in the plays about where the events took place. The latter is relatively easy to explain by the fact that the relations between the characters are more important than their absolute place and therefore the place of the event need not be defined precisely. As for time, the situation is probably the same: the internal time of the event is more important than the external, universal time, and therefore the binding of events at the external time can be ignored in the picture roster.

To sum up, in Swedish and Norwegian versions, the starting point of the image sequencing was the continuity of time, space, and movement, which was then braided by personality description. The starting point of the Finnish versions was the description of the personal relationships, while the variables of time, space and movement remained subordinate. The differences were visible in all comparison pairs. The structures of the films thus reproduced the structures of the case and preposition animations in a very clear manner. The differences in the structure of the films were so large that they were noticeable when viewed one after the other in succession. The Swedish and Norwegian versions followed European film theory (e.g. Burch, 1973; Martin, 1971), while the Finnish versions differed so steadily that it can no longer be considered a coincidence or a lack of professionalism. The European film theory emphasizes the continuity of movement, time and space in a way that fully corresponds to Strømnes theory of continuous motion in three-dimensional space and a constant flow of time. Nor can resource factors be the cause of the differences, because all versions were productions of national broadcasting companies and the resources were in line with it. None of the versions in any country were made with low resources and, for example, there was a lot of work devoted to the productions in order to respond to the circumstances at the time of writing.

REFERENCES

Burch, N. (1973) Theory of film practice. London: Secker and Warburg.

Ihamuotila, P. (1979) Mietteitä suomalaisesta tv-kuvailmaisusta ulkomaanmyynnin kannalta (Thougths about Finnish TV-productions from the point of view of export). Helsinki: Oy Yleisradio Ab, Unpublished manuscript.

Martin, M. (1971) Elokuvan kieli (The language of the cinema). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava.

Strømnes, F.J. (1973) A semiotic theory of imagery processes with experiments on an Indo-European and a Ural-Altaic language: Do speakers of different languages experience different cognitive worlds? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 14, 291-304.

Strømnes, F.J. (1974) No universality of cognitive structures? Two experiments with almost perfect one-trial learning of translatable operators in a Ural-Altaic and an Indo-European language. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 15, 300-309.

Strømnes, F.J., Johansson, A. & Hiltunen, E. (1982) The externalised image. A study showing differences correlating with language structure between pictorial structure in Ural-Altaic and Indo-European filmed versions of the same plays. Helsinki: The Finnish Broadcasting Corporation, Report No. 21.

Comments

2 responses to “The Nordic TV-productions research”

How do differences in mental models across language groups impact the creation and reception of cinema and television productions?

Regard Telkom University

As to how mental models impact the creation of cinema, we have studied only two language groups. The Ural-Altaic group in our studies includes Finnish, and Hungarian. The Indo-European group includes Swedish, Norwegian and English. Our research show clearly that in films made by the Ural-Altaic directors the main focus is on personal relations, even to the point that the description of the environment is almost lacking. In the Indo-European productions the picturing of the environment was very cler and that made it possible for the viewer to track the movements of the persons in the play.

From the animations of the Swedish prepositions and Finnish cases it was predicted that something like this would be the case, but we were not quite sure how the differences would come out in the plays that we studied. As we have not studied other languages in the way we studied the Swedish and Finnish languages, it is impossible for me to say anything about films made by people speaking languages that belong to other language groups. Deducting from the basic theory behind these studies it is very probable that the stuctures of the languages of the film group would be reflected in their productions. That is for some other researchers to verify.

As to the second part of your question, reception of cinema, we have not done any research ourselves. References in this direction had been received from the reception of Finnish film and television productions abroad. These kinds of productions have been alienated there. The best-selling productions were made by Swedish-speaking directors, which would still indicate that it was a language rather than a resource or skill factor. Of course this was in the 1970’s. The situation in the 2020’s is different. One can say that the world has grown smaller. Now it is easier for movie professionals to travel and work abroad and be influenced by professional there. Some Finnish movies by certain Finnish directors have been well received by international publics but that is not very common even nowadays.